I’ve always loved mythic landscapes - the kind that reconnect you with what Ella Saltmarshe calls ‘deep time’. But it was only several years after I moved to North Yorkshire that I realised I lived slap bang in the middle of one.

The moors around us are littered with carved rocks from neolithic times. One of my favourites, just across the valley, is this gorgeous tree of life.

Whenever I’m there, I run my fingers over the carving, and imagine the chain stretching back from me to the people who made it, four millennia ago. I think of how small ‘us’ would have been for them — probably no more than a few dozen people.

Then I think of how, over the hundred and thirty generations since, ‘us’ has become steadily larger. From hunter-gatherers to farmers, from chiefdoms to kingdoms and nations, from villages to towns and cities, from hieroglyphs to html - at every stage, with more communication, cooperation, and complexity.

Finally, I think of the apocalyptic moment we’re living in right now, full of crisis and creativity. It often feels to me like a moment of trial: an initiatory test if you want to frame it in mythic terms, an end of level guardian if you fancy something a bit more contemporary.

So what is it that we’re being tested on? My hunch: it’s all about the size of the ‘us’ with which we identify, in four different ways.

Larger us or them-and-us?

The first is the one we’ve spent most time working on at Larger Us: whether we’re able to come together instead of fracturing into a divided them-and-us.

Sometimes polarisation is helpful. Sometimes it shines a light on problems or injustices that have been ignored for too long. But when it becomes a chronic condition, that’s a whole different story.

I can think off the top of my head of ten instances where polarisation has become so entrenched that consensus seems unimaginable. Here you go: trans rights, abortion, colonial history, Israel-Palestine, immigration, Covid vaccines, defunding the police, attitudes to same sex marriage among churchgoers, Brexit and, well, America.

It’s not just that this kind of division is horrible to live with - from how it affects our families and friendships to how it can leave us feeling increasingly like we live in a foreign country with a whole lot of people whom we mistrust, dislike, or even hate.

It also makes it nigh on impossible to unlock the breakthroughs we need if we’re to make this a good apocalypse. Instead, we either get deadlock; wild pendulum swings (look at US climate policy every time there’s a change of government); or the biggest issues simply going ignored while we all focus on culture wars.

Ironically, we’re often less polarised than we think on actual issues - not just here in the UK, but also in the US. But where we constantly seem to trip up is with affective polarisation: the kind where we polarise not because we disagree, but simply because we feel such antipathy towards the other side.

So that’s one way in which we need to become a larger us. But stick around: we’re just getting started.

Larger us or ‘people like me’?

We humans love being part of groups. As soon as we recognise someone else as a fellow member of a group we belong to, we view them more favourably and give them preferential treatment (psychologists call this ‘in-group bias’).

Which, of course, can be a lot of fun, as evidenced by the look of joy on my 14 year old daughter’s face at being with her people when we went to the Eras Tour…

…or the look of joy you’d have seen on my face if you’d come with me to hear Sasha and John Digweed play last weekend and watched me reunite with my people (warning: strobes!).

While in-group bias might be no big deal among Swifties and ageing progressive house fans, where it becomes a lot less benign is when it starts showing up in politics.

Sometimes the problem is obvious, like when we start feeling superior or even supremacist about our race, gender, social class, nationality, or whatever. Sometimes it’s more subtle, like when biases we may not even be consciously aware of affect things like hiring decisions.

But what we’re really talking about here is whom we do or don’t include in what Albert Einstein called our ‘circles of compassion’: whom we think deserves our care and attention, and whom we relegate to being unimportant or invisible.

Does ‘us’ only extend as far as our family and immediate social circle? What about our neighbours? Or the homeless guy we walk past on the way to the tube? How about people who voted the wrong way in the last election? Or people in small boats trying to cross the Channel or the Med? Or future generations we’ll never meet?

This might sound like abstract philosophising but it really isn’t. Instead, this is the X factor that determines not just what we think of people and how we act towards them, but also what we demand from our politicians, and how we vote.

If ‘shooting the rapids’ of our apocalyptic moment depends on everyone in the boat not just paddling together, as we talked about last time, but also looking out for vulnerable members of the crew, then what that means in practice is whether we’re looking out only for ‘people like me’ or, conversely, for ‘people - like me’.

Larger us or zero sum?

Looking for something to watch tonight? Try Crimson Tide, a thriller set on board an American missile submarine. It’s a proper nailbiter: an intense what-if exploring what stands between us and nuclear apocalypse.

At the film’s heart is the tension between two characters: Captain Ramsey (Gene Hackman), who thinks his job is to follow orders without question, and Commander Hunter (Denzel Washington) who leads a mutiny to prevent Ramsey from launching a nuclear strike because the orders from Washington are ambiguous.

In one scene, before everything kicks off, the two debate nuclear war. Ramsey argues that the key to winning a war is to “ignore everything except the destruction of the enemy”. Hunter’s reply: “I think that in the nuclear world the true enemy can’t be destroyed … in the nuclear world, the true enemy is war itself”.

For Ramsey, war is a zero sum game. One side wins, the other loses – so make sure you’re the winner. Hunter, on the other hand, sees avoiding nuclear war as a positive sum game. As the computer in War Games, another classic nuclear apocalypse near miss movie, puts it: “the only winning move is not to play.”

Right now we are surrounded by issues which force us to choose between a zero sum and a positive sum worldview.

All of us need to prevent climate breakdown (positive sum). But in practice, we’ve had decades of countries and companies slow pedalling or free riding - because they’re concerned about their competitiveness (zero sum).

All of us share a stake in effective ‘guardrails’ on AI, and in slowing development of the technology down until we get them right (positive sum). But in practice, development is surging forward - because everyone fears being left behind by their competitors (zero sum).

All of of us (well, almost all) would benefit from halting arms exports to fragile states, or shutting down tax havens, or levying wealth taxes on the 1% of people who own as much as the bottom 95% of humanity (positive sum). But in practice, none of these things is happening because… well, you get the picture.

It’s tempting to see competition between states and companies as the natural order of things. (People who think like this in international relations call themselves ‘Realists’.)

Me, I think Commander Hunter is the realist in Crimson Tide.

And also that the tension in the world that matters most right now is not between Washington and Beijing, or Jerusalem and Tehran, or Delhi and Islamabad.

Instead, it’s the tension between zero sum and positive sum worldviews that really matters. Not just among politicians in the world’s capitals - but also in the heads of ordinary people like you and me.

Larger us or separate ‘I’?

Which brings us to the fourth and final way in which I think we need to become a larger us - which is all about getting past the idea of ourselves as separate individuals.

This sense of ourselves as separate is in so many ways the keystone of modern life. Science starts from a rigid subject / object split. Economics from the idea that we’re self-interested consumers. Liberalism from the primacy of individual liberty to do what we want. Psychology from looking at the individual self and its needs.

Now, in all sorts of ways, we are reaching the limits of this individualist worldview. In science because of quantum physics. In economics and ecology because of what consumerism is doing to the planet. In sociology and psychology because so many of us are so painfully lonely.

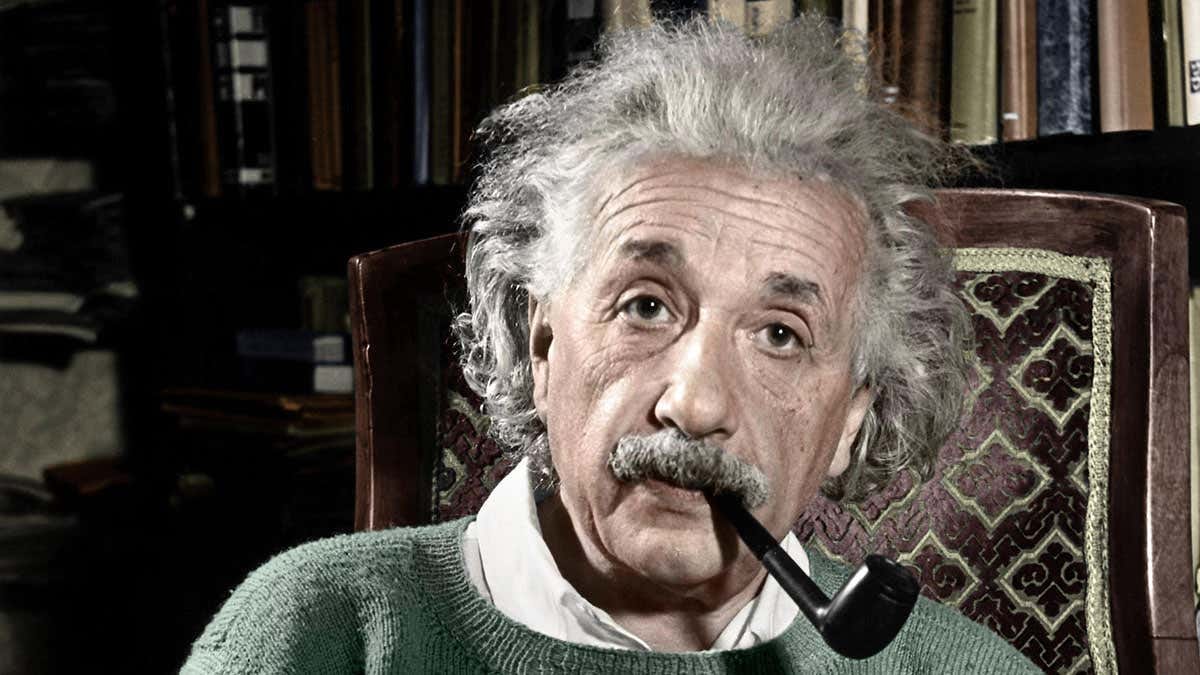

Someone who understood this more deeply than most is Albert Einstein - not just because of his work on physics, but also because of what he had to say about circles of compassion, as we touched on earlier. Here’s the full quote:

A human being is part of a whole, called by us the “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circles of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.

It tickles me that Einstein is just so matter of fact in saying that our sense of separateness is a delusion. It’s not mythology, or a call for new values or whatever. It’s simply a bald statement of what is real and what is not, from the foremost scientist of our age - who also just happens to be going full on mystic on us.

And it also makes me wonder whether the depth of insight that Einstein is bringing to the party here is something that is needed much more widely at this point - and what it would take to enable and support that outcome, if so.

It can seem weird to think that what goes on in our minds can have global impacts. But, as we’ll get into in the next post, understanding the ways in which our states of mind and the state of the world affect and shape each other is very much a key skill for us to master, if we want this to be a good apocalypse.

Links I liked

Worrying about the US election? Me too. But take solace from this lovely thread by Eve Fairbanks on South Africa in the mid-80s. Everyone assumed a “hopelessly inevitable deepening of the conflict”. No one foresaw the miracle that took place.

If you enjoyed the Sasha and John Digweed clip then check out this essay from 2019 by my friend Liz Slade, the chief officer of the Unitarian Church, on the similarities between clubs and churches. (I know exactly what she’s talking about.)

Einstein also once said “I love Humanity but I hate humans” - which is (a) typical of a highly dopamine-oriented personality like his and (b) something you see more often in people who are politically left-of-centre, according to psychiatrist Daniel Lieberman, whom we had on the Larger Us podcast a while back. Who knew?

Such a great piece Alex, thank you!

I LOVE the Liz Slade article and it aligns massively with my own experience, both of church and club culture. I am also going to sit with your idea of the tension between zero and positive sum views - it speaks to my soul and helped me feel as if some pieces are starting to fit together.